February 13 – May 10, 2019

Small Worlds explores the ways contemporary artists use miniatures to inspire awe, whimsy, and even dread. These artists either create or employ found miniature figures, rooms, and landscapes, displaying them through photographs or sculptures. The resulting scenes, reminiscent of our childhood playthings, can recall in us that sense of wonder for the world around us, but also call our attention to the dark forces hidden beneath the seduction of the small. As our inherent attraction to the miniature sucks us into the imagined world of the artist, real-world traumas such as violence, displacement, and environmental disaster are brought to our attention in intricate and intimate ways.

Joe Fig and Minimiam (Akiko Ida + Pierre Javelle) each communicate the joys of creating. Fig seeks to understand famous artists by constructing obsessively meticulous models of their studios, providing viewers unique access to the creative process. Under the joint name Minimiam, photographers Ida and Javelle merge their love for art and food by arranging miniature train figures with fruit, pastries, and ice cream to create whimsical scenes of recreation, labor, and culture.

Sally Curcio and Allison May Kiphuth translate their love of landscape into enchanting capsules. Curcio creates modern renditions of snow globes made from found objects. Some recreate real sites such as New York City’s Central Park, while others become other-worldly fantasies. Kiphuth is inspired by her travels and her New England environment to integrate watercolors into “uncontained dioramas” that communicate her passion for the natural world.

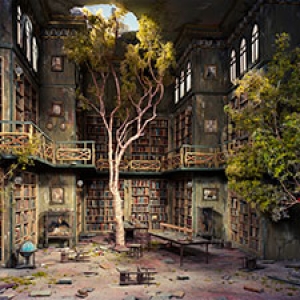

Thomas Doyle and Lori Nix + Kathleen Gerber depict the human world eerily overtaken by nature. Doyle constructs models of suburban homes subject to sudden, inexplicable environmental disasters that displace and bewilder their inhabitants. Nix + Gerber create and then photograph intricate scenes of cities and sites of arts and culture reclaimed by natural forces after humans have disappeared.

Corin Hewitt and Mohamad Hafez communicate the dark psychological charges evoked by the buildings that constitute “home.” A native Vermonter and descendant of a family of artists, Hewitt has constructed a modified miniature version of his family’s cabin in East Corinth, Vermont, in which outer and inner walls are manipulated to question the distinctions between public and private, inside and outside. Hafez’s heart-wrenching models of Syrian buildings, destroyed by war but displaying signs of life and hope, reflect the artist’s longing for a home transformed by turmoil.

Two artists based in Vermont recreate in miniature the museum activities of collection, classification, and display. Brian D. Collier developed The Collier Classification System for Very Small Objects, a taxonomy used to name any solid, non-living thing smaller than 8mm x 8mm x 25mm. Visitors can peruse The Traveling Museum of Very Small Objects and make their own contributions to the collection. Matt Neckers created the Vermont International Museum of Contemporary Art + Design (VTIMoCA+D), a series of galleries—many of them mobile—full of miniature artworks. VTIMoCA+D galleries in antique suitcases and a vintage fridge will be on view. The latter will be interactive, demystifying the act of curating for Fleming visitors.

Whether conveying the simple joy of a clever visual pun, or exploring some of the greatest challenges facing our world, art in miniature compels us to look closer, in awe at the skill, enchanted by the size, captivated by the message.

Special thanks to all of the artists and their galleries for their generous assistance. This exhibition is supported by the Kalkin Family Exhibitions Fund and the Walter Cerf Exhibitions Fund.

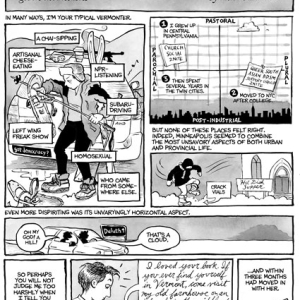

Thomas Doyle’s “Staging Area,” 2014

Thomas Doyle, Staging Area (detail), 2014. Mixed media, 21 x 20 x 4 ½ inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Lori Nix & Kathleen Gerber’s “Library,” 2007

Lori Nix / Kathleen Gerber, Library (detail), 2007. Archival pigment print , 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy of ClampArt, New York City. © Lori Nix/Kathleen Gerber

Mohamad Hafez’s “Hiraeth,” 2016

Mohamad Hafez, Hiraeth (detail), 2016. Plaster, paint, antique toy tricycle, found objects, rusted metal, and antique wood veneer, 61 x 35 x 21 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Sally Curcio’s “Happy Valley (Fall), 2016

Sally Curcio, Happy Valley (Fall), 2016. Beads, flocking, fabric, thread, plastic, pins, painted wood frame, and acrylic bubble. 12 x 12 x 6 inches. Smith College Museum of Art, Purchased with the Deaccession Acquisition Fund 2016:22-2.