What does it mean for a small island at the eastern edge of Canada to colour its nature ‘Celtic’, as it does with the heavily promoted, annual international festival called Celtic Colours?

The Cabot Trail winds its rollercoaster-like way along or near the coastline, offering views of mountains, cliffs, stunning drops to the shore and its expanse of ocean, and of roadside gift shops and hints of the (now much quieter) fishing villages that still span much of the coast.

As the road’s eastern arm crosses northward across the park boundary, an interesting transformation occurs, as all traces of ‘lived culture’ disappear and are replaced by what Alex Wilson (1992) referred to as ‘the culture of nature’: signs directing visitors to scenic overlooks, roadside parking areas, and numbered trailheads, all stitched together by the familiarly minimalist semiotic of yellow-on-brown National Parks signs – a question mark indicating an information booth, an upside-down ‘V’ for a camping area, a stick-figured, circle-headed, binocular-holding ‘man’ indicating a lookout point, and so on. As the highway winds through the area of North Mountain and South Mountain, both the lookout points and the cars in their parking lots increase in number, and, at the height of fall, the foliage blazes in remarkable colours from the wall of highlands facing the cars and onlookers.

A dozen or so scenic viewpoints later, as the visitor departs the park’s western boundary, the landscape seems suddenly ‘real’ again, with the white and pastel-coloured Acadian homes, with their gently-pitched, seaward-sloping roofs, straddling the road, and the hardware stores, doughnut shops, and bed-and-breakfasts of the seaside village of Chéticamp. It is almost as if a black-and-white – or green – screen has suddenly burst into living colour, abounding in the lived culture of human livelihoods being made, with even the optimistic economic sign of fishing boats in the harbour. Or is it the other way around, with the national park’s muted signage highlighting the living colour of its scenery, while this thoroughly ‘cultured’ world outside it serves as its black-and-white foil?

Cape Breton as a New World Scotland

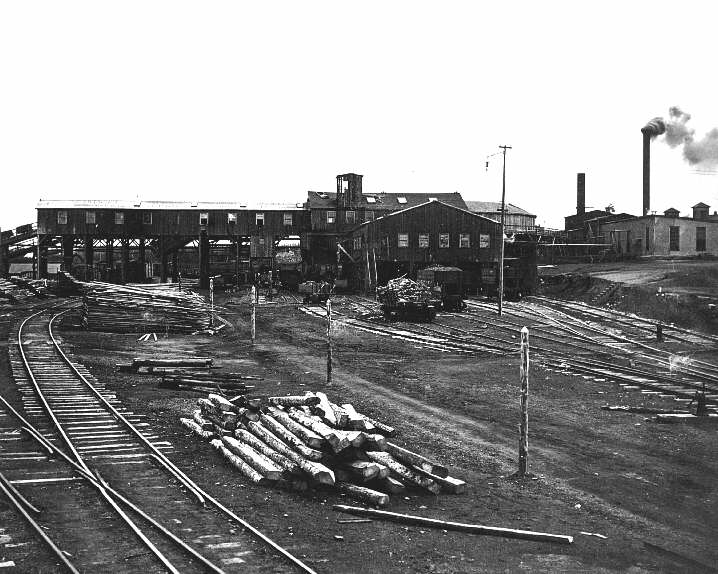

Historian Ian McKay (1992, 1993, 1994) has exhaustively documented how urban-based cultural producers and government tourism managers, during the second quarter of the twentieth century, produced the image of Nova Scotia as a ‘New World Scotland’ and a ‘timeless’ place of rugged, hearty, but simple ‘country folk.’ . . . With the steel and coal industries centred around Sydney Harbour and its vicinity, Cape Breton at the time housed the largest industrial complex in the Atlantic Provinces.

Following his ascent to the premiership, Premier Angus MacDonald vigorously pursued this vision of Nova Scotia as the ‘last great stronghold of the Gael in America’ (MacDonald 1937) and ‘greatest outpost of Celtic Scotland in the whole world’ (MacDonald 1948). To make Cape Breton more attractive to that ‘whole world,’ MacDonald developed the Cabot Trail highway, deeded a part of the northern cape to the federal government for the creation of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, and presided over the founding of St Ann’s Gaelic College (with its nostalgic-romanticist Hall of the Clans) and the construction of the Lone Shieling, a replica of a Scottish Highland crofter’s cottage designed after one mentioned nostalgically in the anonymous poem ‘Canadian Boat-Song,’ a poem which had already been recited by generations of Nova Scotia school children. MacDonald went so far as to suggest to his minister of mines and resources, J. A. McKinnon, that Cape Breton Highlands National Park foresters wear Scottish kilts and replace the green forester’s bonnet with the ‘Scottish blue’ (McKay 1992:29). Nature was thus to be firmly associated in the visitor’s mind with the tartan and the kilt, the cultural trappings of an ethnicity reconstructed in response to the pressures of tourism (McKay 1992:45).

Paradoxically, while a ‘merry tartanism covered Nova Scotia,’ the official neglect of the needs of Gaelic speakers led to a near-disappearance of the Gaelic language in the province (McKay 1992:34). As McKay puts it, MacDonald wrote the ‘saga of the Scottish soul into the province’s collective memory – on its roads and signs, its festivals and gatherings’ (19).

Celticity Ablaze

Celtic Colours is the third largest Celtic festival in the world, topped only by Glasgow’s Celtic Connections and the Festival Interceltique de Lorient in Brittany, France. The ‘colours’ are a play on the implied interpenetration of the island’s cultural and natural heritage, both of which will greet visitors to the island in full bloom at this autumnal harvest of artistic events, ceilidhs (gatherings), square dances, and celebrations.

But what makes the music ‘Celtic’? Is it the instrumentation, its tonal qualities and sonorities, its vocal delivery, its lilting, dance-like rhythms and repetitive variational forms? If instrumentation, is it the bagpipes, tin whistles, and fiddles, or the strumming guitars, electric pianos, and synthesizer washes that increasingly fill in its textures? Or is it the ethnic affiliations, languages spoken or sung, or ‘temperaments’ of its performers?

The festival is a place Celticity and pan-Celtic identities are displayed, performatively enacted, and transformed. ‘Celticity’ is redefined both more tightly or centrifugally — with pride of place given to Cape Breton, with its unique and localized fiddle-playing styles, pianistic accompaniment, and step-dance traditions that have disappeared even in the Scotland in which they ostensibly originated – and, at the same time, more expansively, extending outward into the Latin Transatlantic (e.g., via Spain’s bagpiper Carlos Nunez, who claims to have met Celtic bagpipers while traveling in Cuba), the American South (through the Acadian Diaspora, whose musical culture shows mutual influences with and on Gaelic musical traditions), the multi-ethnic world of ‘Aboriginal music’ (through such artists as Mi’kmaq Cape Bretoner Lee Cremo), and into the by-roads of ‘world music’ through the various collaborations of such ‘Celtic music’ giants and crossover artists as The Chieftains and Afro Celt Sound System.

Cape Breton Island is thereby repositioned from being a ‘rural backwater’ or, at best, a peripheral outpost of cultural conservatism to what is now a lively and progressive cultural crossroads – a place that seems on its way to becoming what Bruno Latour calls an ‘obligatory passage point’ within the transnational networks of Celticist cultural marketing. What were once local, family- and community-based performance traditions have been extended or mutated into global networks of musicianship, fandom, style, and commerce. Renamed ‘Celtic,’ the music of Cape Breton performers, from the vocal stylings of Rita MacNeil to the rocked-up performance antics of Ashley MacIsaac, comes to signify the ‘timeless’ tradition, expressive energy, and natural and cultural ‘colours’ of the island itself.

“Before we were Celtic,” writes Frances MacEachen (1997b), editor of the English-Gaelic quarterly Am Braighe,

we were Scottish. Not so long ago the promoters wanted us to adorn kilts and bellow clan cries. Now, it seems, we are more photogenic with fiddles and perhaps a less ethnic look: cosmopolitan rhythms linked with ancient tunes… world music… now we’re talking. Of course, the almost-fallen-down barn makes a nice backdrop now and then. The point is that all these images are based in myth and marketing, nothing real.”

But what is real and what isn’t? The pre-Columbian Mi’kmaq population maintained trading networks extending down the coast and into the interior of the continent. When they entered into trading relationships with Europeans, their fur trapping activities became nested within an international network that resulted in substantial reduction of fur-bearing species and in other ecological transformations.

Nineteenth and early twentieth century Cape Breton rural life was similarly integrated into larger market networks. Livestock, butter, crops, and timber from more prosperous ‘frontland’ farms were sold to markets supplying the coastal fishing and mining settlements (as well as Halifax and St. John’s, Newfoundland), which in turn supplied international markets with cod, coal, and other staples. Farmers and squatters on the less prosperous ‘backlands’ barely eked out a living and regularly resorted to seasonal migrant labour in coastal fishing towns, coal mines, or as far away as Halifax and Boston. Beef farmers faced competition from the American Midwest, just as local fishing and mining industries responded to the rise and fall in world prices for their goods (Hornsby 1992; Donovan 1990; Pryke 1992).

‘Myth and marketing’ may seem less real than the musical and cultural traditions passed down from generation to generation because those cultural traditions were never marketed to larger consumption networks the way the staples of Cape Breton’s economy have been. Today that situation has changed: song and dance have become the new cod and coal for many Gaelic Cape Bretoners. This point is neatly underscored by the fact that the current Minister of Tourism, Culture, and Heritage for Nova Scotia, Rodney Macdonald, happens to be an excellent young fiddler from Inverness County. [Note: Macdonald served in this role in the early 2000s, and from 2006 to 2009 was the Premier of the Province of Nova Scotia.]

Cape Breton includes islanders of French or Acadian, English, and Irish ancestry, as well as an indigenous Mi’qmak population and a potpourri of South and East Europeans, Lebanese, African-Canadians, and other ‘hyphenated Canadian’ ethnicities centred in the urban areas around Sydney. Not surprisingly, there is competition for scarce state resources among these different groups, and potential contention around who speaks for the island.

The Mi’kmaq have the longest-running claims to Cape Breton Island, or Unama’ki, as it is known in their language. With a population of some six thousand concentrated in the island’s interior near the saltwater Bras d’Or Lakes, the Mik’maq have played a disproportionately visible role in a series of recent environmental struggles. In an alliance with non-Native environmental groups, the Mi’kmaq played a critical role in a campaign against the forestry practices of Swedish multinational Stora, and later mobilized decisive opposition against a proposed granite quarry on Kelly’s Mountain (Kluskap Mountain) (see Hornborg 1994, 1998; Mackenzie and Dalby 2003; Stackhouse 2001). Attempts to reinscribe a Mi’kmaq identity onto the landscape, outside of their reservations and towns, have included the proposed construction of Kluskap Kairn to memorialize those who had fallen in the four centuries of ‘protracted holocaust’ since the arrival of white Europeans (Mackenzie and Dalby 2003:319)

In the end, the question may be: when you drive the Cabot Trail and see these colours, what do you see?

The above is excerpted and revised from “Colouring Cape Breton ‘Celtic’: Topographies of Culture and Identity in Cape Breton Island,” Ethnologies 14.5 (2005). To read the full article, click here or here.