Understanding Space and Society

The interplay between space and identity within urban settings is particularly apparent with Tempelhof Field. In understanding larger theories on how cities and spaces contribute to senses of belonging, I look to scholars such as Edward Soja, Doreen Massey, and John Urry, for their contributions to the socio-spatial dialectic.

Soja’s concept of “thirdspace” highlights the multifaceted nature of urban landscapes, emphasizing their role as both physical environments and symbolic arenas of social interaction. 1

The idea of “place as process” underscored by Massey, highlights the dynamic nature of urban spaces, shaped by ongoing social relations and power dynamics.2

Urry’s research on mobilities explores how movement and transportation systems influence urban experiences, impacting individuals’ sense of identity and belonging within the city.3

Together, these theoretical frameworks shed light on how cities, through their spatial configurations and social dynamics, shape individuals’ perceptions of belonging and identity. This understanding is vital for the assertion of my conclusions, which examine the ways Tempelhof Field shapes individuals’ and groups’ sense of belonging in Berlin, their connections to one another, and their relationship to this iconic physical environment.

Civic Participation in Berlin

Understanding civic participation in Berlin’s land-use and development planning processes since the 1970s is vital to understanding how Berliners participate in development processes today.

The past five decades illustrate two important realities that are relevant to our understanding of citizen and government involvement in the planning of Tempelhof Field’s present and future:

- Grassroots protest and civic participation are vital elements to Berlin’s land-use planning processes, of which some infrastructure exists to facilitate discussion between civic groups and government planners.

- Economic trends have necessitated a level of outsourcing by government, which means the shifting of responsibility to community participation for the upkeep of urban spaces.

Berlin is a city-state of Germany, with its state government, in German the Senat (Senate of Berlin), operating above a number of city districts, Bezirke. Both of these entities participate in land-use planning for the city, and share interests with federal bodies. In the 1970s, the economic growth and energy priorities at the federal level were shared with state and local governments in West Berlin. With the decline of economic prosperity in the following decades, social movements demonstrated a growing critique of growth and issues of quality of life.4 West Berlin was acutely faced with what many call the “ecology-economy conflict”, which prompted the nationwide rise of the environmental movement.5 6

Urbanization highlighted the challenges of expansion in a confined space; industry and population were forced to coexist and it became apparent that there were insufficient means to disperse the negative impacts. Local groups became increasingly opposed to government industrial initiatives that were at the expense of natural environments. For example, former energy company BEWAG proposed the Reuter-West power plant in the middle of one of Berlin’s largest forested areas in order to avoid residential spaces. They were immediately met with enormous and forceful citizen protests. The energy issue most clearly aggravated challengers of the growth mentality, but a wider array of movements were concerned with women’s issues, war opposition, and labor concerns.7 Thus, people began to depart from the technocratic mentalities of the past and adopted a more widespread position that only a democratic decision making process could produce adequate policy.

The movements of the 1970s and 1980s led to a more “activist citizenry” and a more participatory planning process.8 Despite many changes to the institutional planning process, grassroots protest has remained a frequent and necessary piece of the planning process for Berliners. Berlin’s grassroots mobilization in the past decades was seen as a way to challenge the encroaching “industrial-bureaucratic growth machine” situated within a larger context of German protest against state industrialization projects.9 The 1970s saw large formation of new social movements and Bürgerinitiativen (citizen’s initiatives) across Berlin and Germany, a trend that persists to this day.10 These protests even led to the founding of green and alternative parties such as the Alternative Liste Partei, which won its first seats in 1981. Since these initial movements, a variety of building, planning, and legislation processes mandate civic involvement in planning, and additional requirements like environmental impact testing were implemented.11

Reunification of Berlin meant rethinking city planning altogether, and the 1990’s stagnating economy meant more control over space by the development authorities and reliance on public investment, neither of which were processes the Senat or local government could effectively monitor. Initiatives like the City Forum as an advisory body were incremental enhancements of citizen participation in formal planning, but no institutionalized forum for conversation between citizens and politicians. Thus, grassroots mobilization remains an enormous part of Berlin’s planning conversations, a dynamic we will see well exemplified in the context of Tempelhof Field.

As a part of the ecology-economy conflict and widespread environmental movement, people also developed a variety of methods to combat state control of urban greenery.12 These means of protest included greening of patios and backyards, public squating, and use of void spaces to hinder development.13 In Rosol’s examination of urban gardens in Berlin, community run spaces are a prime example of the local government’s withdrawal from earlier “welfarist functions” towards a supplemental strategy that involves community engagement as a cheap outsourcing solution.14 The City of Berlin’s unfortunate budget situation meant the unwillingness or inability to fund much collective infrastructure, which often meant “land fell vacant”, enabling “possibility for interim uses like gardens”.15 An examination of community gardening in Berlin finds a clear shift from gardening as strongly connected to urban social movements, to “community gardening as a form of volunteerism or the provision of social services”.16 It is also important to note the provisional asterisk; with impermanence underscoring their existence while the possibility of development by state land owners once funds are accumulated.

This turn is not to negate the progressive and liberating nature of community gardens. A growing number of them in Berlin, created according to the needs and ideas of its users make them starkly different from traditional city parks.17 While Rosol situates community gardening participation within a broader neoliberal handoff of state responsibilities to civil society, user-creation makes community gardens both critiques of, and alternatives to, more traditional state implemented open spaces.18

The co-construction of green space by state and non-state actors in community gardens is a useful example for understanding dynamics of interest in Berlin’s open green spaces. The role of the community voluntary sector may aim to close the gap that withdrawal of funding create, while reflecting the specific needs and desires of gardeners. In Germany, community gardens are distinct from typical German Schrebergärten (allotment gardens) and are planned, designed, and built collectively by local residents. Another distinction is their function beyond food, as most Berlin community gardens are decidedly not food producers. Rather their benefits are focused on potential aesthetic, recreation, and environment functions, or addressing public concern for “ugly” neglected spaces.19 For Bezirke administrators, “using the unpaid labor of local residents to turn urban wastelands into public gardens,” is a sustainable and cheaper alternative to maintaining gardens than through employment of city staff.20 The motives of community gardeners themselves however, are centered on enjoyment, aspects of socialization and community building, dissatisfaction with existing green spaces, and the desire to provide their kids with safe and enjoyable spaces. Additionally, health aspects of gardening, access to nature, feelings of responsibility, and pedagogic motives make gardeners motivated agents of change.

Community gardens in Berlin are an apt example of interaction between civic groups and state and local government can help us understand the history and broader contexts of how Berlin’s open green spaces are co-created, maintained, or threatened. Examples like the battle over Reuter-West provoked ongoing discussions about what spaces in the city are most integral to quality of life.21

Civic Participation and the Field

Public participation on Tempelhof Field began long before the decisive 2014 referendum. After the closure in 2008 following a referendum in which only 22% of the public participated, the site was opened to Berliners in May of 2010. This was the first referendum since the 1995 Berlin constitutional amendment that allowed direct voting and made citizen participation in urban development binding.22 The Bürgerinitiative flugfreies Tempelhof (BIFT) (flight-free Tempelhof), was one of the first civil initiatives to speak for the closure of the airport. In 2008, the Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung, Bauen und Wohnen (Senate Department for Urban Development, Building and Housing) proposed the concept plan “Tempelhof Freiheit” (Liberty of Tempelhof). This plan proposed an urban forum of culture and activity in the old hangar building and recommended the construction of thousands of apartments on the edges of the field, to be constructed by 2025.

Prior to its opening, several public discourse events had been completed regarding what to do with the field, but none of them concerned the topic of housing construction on the site, which was one of the public’s main concerns.23 In 2008, an open call for Pioneer Areas and ideas was held, of which some chosen projects remain today. The conceptualization of these spaces was transitory, and permanence was not legally guaranteed. Two rounds of public surveys were held to gauge public impression and beliefs about the field’s future. In 2009, 13,000 citizens were able to see the not-yet-open airfield by special bus tour.

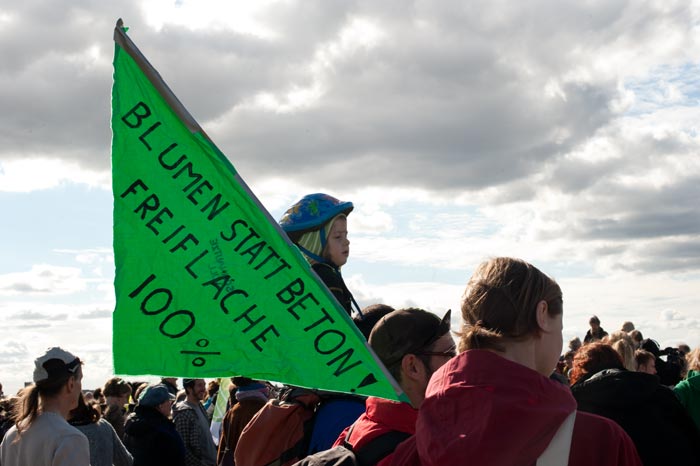

The field reopened to the public on May 8th, 2010, nearly unchanged after the 2 years since the final flight departed. Eighty thousand people visited the field on its first day open, and its future use quickly became a large issue within Berlin. Citizen groups such as Squat Tempelhof and 100% Tempelhofer Feld were founded in 2009 and 2011, respectively, and began advocating for the preservation of the field.

Christina Palitzsch (2012). Umbruch Bildarchiv.

Christina Palitzsch (2012). Umbruch Bildarchiv.

Between 2010 and 2013, the Senate gathered information on public ideas for the field in its process of creating the masterplan for Tempelhofer Freihet. The plan was presented to the public in March of 2013 and opened to public discussion and a series of public participation events.

Open dialogue sessions received feedback from the over 500 participants; concerns, ideas, wishes, and more were given to the Senate department. No constructive feedback was returned to citizens, and the only response by the city was: “the results have been used for the planning process”.24

Conflicts of re-use for the field reached a high in 2014, when the referendum initiated by 100% Tempelhofer Feld went to a vote. The two options on the ballot were as follows:

- Preserve the field as 100% open space

- Follow the city government’s vision and develop in accordance with the Tempelhof Freiheit Masterplan.

The government actually began construction in 2013, despite the forthcoming referendum, and argued it could not back the proposed conservation bill, citing “the urgent housing situation in Berlin,” necessitated not waiting for the “lengthy procedural and participatory pre-arrangements” of the referendum results to conclude.25

The Volksentscheid passed with 46% voter participation (1.1 million people), with a majority in favor of protecting the field passing in all city districts. 739,124 Berliners voted in favor of protecting the field, a binding result that went into effect the following month.

Regardless of the result of the referendum, public participation in the decision making process leading up to it left many residents feeling dissatisfied. Anthropologist Marius Mailänder was in attendance of the citizen talks of May 2012, his notes from the event illustrate discontent with the selection of topics put up for discussion:

“The goal of the dialogue was twofold: informing the participants about the general status of the plans and speaking about the wishes and suggestions of the people living in the adjacent district of Neukölln. (…) There would be small groups in which the citizens could discuss four predefined topics: leisure time, playgrounds, and sport; tranquility and recreation; environmental education; and urban gardening. (…) Many people protested and said that these were not the relevant topics. One person commented that most people had come to discuss the edges of the field and the imminent construction development and not ‘what fucking colour the park benches are supposed to have.’ (…) He further said that ‘if the government does not want to talk about the topics that everybody deeply cares about, then the whole event would not be about citizen participation.’ He got a lot of applause and approval.“26

What public sentiment made clear was the feeling that the government neither listened to, nor validated, resident fears about gentrification, rising housing costs, and eviction from their neighborhoods.27 Major public concerns regarding development and subsequent gentrification of Schillerkiez, a low-income, diverse neighborhood to the east of the field remained consistent during planning discourses. The above public participation processes did little to calm public fears and remained a top-down development plan. Neither were the 2014 referendum results immediately respected, with the 2015 version of the Flächennutzungsplan (development usage plan) (the city’s legally binding development plan), had not been updated to reflect the referendum results.

Today, the participation model consists of a three-pillared approach to ensure fair participation in the decision making processes of Tempelhof Field’s future. The three bodies include the field coordination group, the field forum, and thematic workshops. The participation platform allows citizens to stay informed and get involved in the process.

The 14th Field Forum. Kathleen Wächter, 2023, “#Feldliebe – beim 14. Feldforum,” Tempelhofer Feld, https://tempelhofer-feld.berlin.de/.

- Edward W. Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ↩︎

- Doreen Massey. Space, Place, and Gender. NED-New edition. University of Minnesota Press, 1994. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttw2z. ↩︎

- John Urry, Mobilities. Polity Press, 2007. ↩︎

- Carol Hager, “Three Decades of Protest in Berlin Land-Use Planning, 1975-2005,” German Studies Review 30, no. 1 (2007): 55–74. ↩︎

- Ibid., 56. ↩︎

- Samuel Holleran, “From Graves to Gardens: Berlin’s Changing Cemeteries,” City 27, no. 1/2 (2023): 250, doi:10.1080/13604813.2023.2173401. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Carol Hager, “Three Decades of Protest in Berlin Land-Use Planning, 1975-2005,” German Studies Review 30, no. 1 (2007): 55 ↩︎

- Ibid., 56. ↩︎

- Marit Rosol, “Public Participation in Post-Fordist Urban Green Space Governance: The Case of Community Gardens in Berlin,” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 34, no. 3 (2010): 551, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00968.x. ↩︎

- Hager, Carol. “Three Decades of Protest in Berlin Land-Use Planning, 1975-2005.” German Studies Review 30, no. 1 (2007): 55–74. ↩︎

- Marit Rosol, “Public Participation in Post-Fordist Urban Green Space Governance: The Case of Community Gardens in Berlin,” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 34, no. 3 (2010): 551, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00968.x. ↩︎

- Ibid., 551. ↩︎

- Ibid., 549. ↩︎

- Ibid., 558. ↩︎

- Ibid., 559. ↩︎

- Marit Rosol, “Community Volunteering as Neoliberal Strategy? Green Space Production in Berlin,” Antipode 44, no. 1 (2012): 239–57, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00861.x. ↩︎

- Ibid., 240. ↩︎

- Ibid., 245. ↩︎

- Ibid., 247. ↩︎

- Samuel Holleran, “From Graves to Gardens: Berlin’s Changing Cemeteries,” City 27, no. 1/2 (2023): 247–61, doi:10.1080/13604813.2023.2173401. ↩︎

- Carolin Genz, “The Wide Field of Participation: An Essay on the Struggle for Citizen Participation and the Future of the Tempelhof Field,” Journal of Urban Life (2015): 9. ↩︎

- Ibid., 10. ↩︎

- Ibid., 11. ↩︎

- Ibid., 13. ↩︎

- Ibid., 14. ↩︎

- Ibid., 14). ↩︎