Photo by Clara Feldman

Urban green space (UGS) is a crucial part of functioning, livable cities.1 Urban green space offers residents recreation and health opportunities, conservation of biodiversity, contributes to the identity of a city, provides natural solutions to urban technical problems, improves quality of life, and offers a variety of nature experiences within cities. Urban green spaces have even been integrated into planning from a public health perspective, stressing their role in facilitating healthful exercise and connection to nature.2While benefits of UGS are well documented, there are many challenges to understanding their development, management, and maintenance. Limited budgets and the emphasis on high-density cities across Europe often places urban green spaces at lower priority status.3

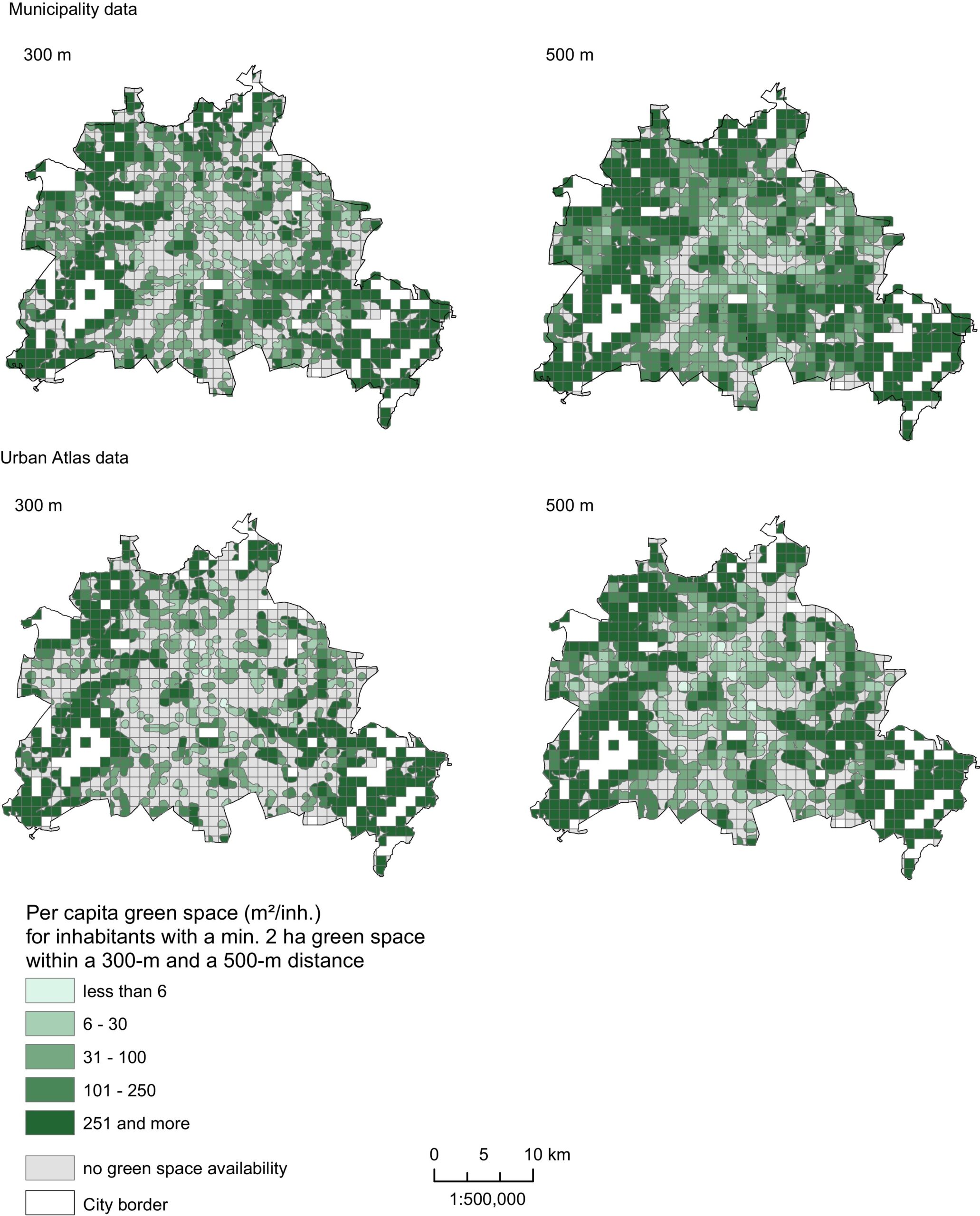

Despite this, UGS instances across Europe and Berlin have risen. Berlin experienced dramatic socioeconomic changes after 1990, and with declining population and industry, the city saw a notable rise in brownfields.4 Today, Berlin’s share of green and open space in the city rests at around 47.7 percent of its nearly 900 kilometer square area, including bodies of water and forested areas.5 Sixty-eight percent of the population lives within 500 meters of a two-hectare green space, with 30% within 300 meters of those spaces.6

Access to urban green spaces is also noted to reduce the environmental burdens of air pollution, noise pollution, and heat risk. Berlin is no exception to the environmental inequity that puts higher rates of environmental burdening on neighborhoods of lower socioeconomic status.7 Increases in housing costs and population growth potentially aggravate the existing social inequalities with regards to housing and environmental conditions, with the spatial concentration of high burden being in the inner city.8 Planning recommendations made on the basis of spatial-distribution studies regarding environmental injustice include support for the existence of more UGS. But it is important to note that distributional justice of urban green space is not solely dependent on its availability, as differences in use are observed in different groups.9

Making sure UGS meet the needs of city residents requires a multifaceted and interdisciplinary approach in planning. Overall, the expansion of UGS is beneficial for its various societal benefits and ecosystem regulation services, particularly the mitigation of pollution and associated health benefits like reduced stress and psychological well being.10 While formal planning for expanding urban green space is critical, informal UGS play an immensely important role in creating a network of green space that benefits cities and their inhabitants.

The importance of UGS is not the primary focus of this study, it’s important to understand the basic benefits of urban green space in cities and some of the implications for planning. As we will investigate further, the availability of green and open space is a central factor in the conception and valuation of Tempelhof Field.

A (Brief) Modern History of Green Space in Berlin

Mid 19th Century:

Before the founding of the German Empire, urban planning in Berlin (including the development, maintenance, and use of urban green space), was controlled by the Prussian state.

Around 1840, the only true available recreation space for Berlin residents was the promenade of Unter den Linden and the Großer Tiergarten.

Berlin’s real beginnings with green space came in 1870, when the founding of the German Empire meant the establishment of the first “Park Deputation”.11

1870-1920:

With a new parks and gardens administration, green space in Berlin began to grow. The office of the Park Deputation oversaw the planning and expansion of new green spaces, and planted many trees throughout the city. The green spaces of this time were called “people’s gardens,” and meant to be, “places of exercise, recuperation, of sociable conversation, and also of the enjoyment of nature, as well as the formation and refinement of manners”.12

As Berlin’s population grew, so did calls for improved urban planning on all fronts, including expanding urban greenery. Between 1910 and 1920, many new parks were planned and built.

1920 – 1948:

Following the first World War and the formation of the Weimar Republic, the municipality of Greater Berlin was established and had 3.8 million inhabitants. In 1921, only 1.5% of the Berlin city area was green space, parks, and public decorative squares.13

Creating jobs for the large unemployed population in the post war period, the Mayor of Berlin established an emergency program, funding the construction of parks, playgrounds, and sports fields.

One of the multiple public parks created in the 1920s was Volkspark Tempelhofer Feld (Tempelhof Field Public Park). At the time, it was 30 hectares (74 acres), and only lasted as a public park from 1921 to 1927.14

These public parks served a very specific and special variety of opportunities for use:

“All strata of the population were to be provided with the space and the opportunity to spend time in the public parks at any season of the year. They were to be able to enjoy games and sports there, but also to find space for tranquil resting. Instead of ‘decorative value,’ the public parks were to provide ‘use value’”.15

In the aftermath of World War 2, Berlin’s park system suffered the “greatest setback in history”.16 Thousands of hectares of green space were destroyed during the war, and forested area was cleared in its aftermath for energy uses.

In 1948, amid a rubbled landscape, the city lost its unity.

Berlin’s division into East and West meant the city’s landscape would develop unevenly for the next four decades.

East Berlin 1948-1990:

Efforts in East Berlin were primarily focused on war recovery until 1950. Between 1950 and 1970, urban planning funds went primarily to the construction of sports facilities for national and international youth meetings, as well as some construction of green areas in public and residential housing spaces.

In the two decades before the fall of the Berlin Wall, a major residential housing construction program took place, and green spaces were planned with these housing units as context. A publicly backed campaign in 1982 beautified 10,000 courtyards in Berlin by 1985.17

West Berlin 1948-1990:

The green development of West Berlin began just after the war, when the Main Department of Green Space and Horticulture/Landscape Gardening was established in 1948. In 1949, the Urban Planning Law of the State of Berlin passed.

The green-space plan of this land-use plan was established in 1959 and confirmed by the House of Representatives in 1960. As a result of this plan, the city’s development was to be constructed as a network of interconnected green strips that accounted for existing infrastructure and scenery, not as disparate green spaces.18

In the period of 1966 to 1980, major city redevelopment and transportation system construction occurred, often at the expense of open spaces (particularly farmland and allotment gardens). This resulted in heavy public criticism, made worse by West Berlin’s position of isolation at the time. Laws and statues followed this pushback, trending towards the conservation of urban green space.

Between 1980 and 1990 multiple new land-use plans and green space programs went into effect. In 1984, a species protection program based on the Berlin Nature Conservation Law was created in addition to the land-use plans.19

Untied Era: 1990-1999

A common administration was established for the city shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. A landscape program was set up and came into effect in 1994.

2000 and Beyond:

In the 21st century, Berlin’s green spaces have increased; many new parks, compensation landscapes, and the expansion of existing parks have made the city one of the greenest metropolitan cities in Europe with over 2,500 parks.20

- Kabisch, Nadja, et al. “Urban Green Space Availability in European Cities.” Ecological Indicators 70 (November 2016): 586. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.02.029. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.uvm.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,url&db=aph&AN=117440683&site=ehost-live&scope=site ↩︎

- Carpenter, M. “From ‘healthful exercise’ to ‘nature on prescription’: The politics of urban green spaces and walking for health.” Landscape and Urban Planning 118 (2013): 120–127. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.02.009. ↩︎

- Kabisch, Nadja, et al. “Urban Green Space Availability in European Cities.” Ecological Indicators 70 (November 2016): 587. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.02.029. ↩︎

- Ibid: 588. ↩︎

- Hölzl, S. E., et al. “Vulnerable socioeconomic groups are disproportionately exposed to multiple environmental burden in Berlin – implications for planning.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 13, no. 2 (2021): 336. doi:10.1080/19463138.2021.1904246. ↩︎

- Kabisch, Nadja, et al. “Urban Green Space Availability in European Cities.” Ecological Indicators 70 (November 2016): 591. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.02.029. ↩︎

- Hölzl, S. E., et al. “Vulnerable socioeconomic groups are disproportionately exposed to multiple environmental burden in Berlin – implications for planning.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 13, no. 2 (2021): 342. doi:10.1080/19463138.2021.1904246. ↩︎

- Ibid: 343 ↩︎

- De la Barrera, Francisco, et al. “People’s perception influences on the use of green spaces in socio-economically differentiated neighborhoods.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 20 (2016): 254–264. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2016.09.007. ↩︎

- Hölzl, S. E., et al. “Vulnerable socioeconomic groups are disproportionately exposed to multiple environmental burden in Berlin – implications for planning.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 13, no. 2 (2021): 345. doi:10.1080/19463138.2021.1904246. ↩︎

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “The State-Directed Development of Urban Green Space in Berlin until 1870” n.d. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/urban-green-space/history/urban-green-space/to-1870/ ↩︎

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “The Municipal Development of Urban Green Space, 1870 to 1920” n.d. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/urban-green-space/history/urban-green-space/1870-to-1920/ ↩︎

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “Municipal Development of Urban Green Space, 1920 to 1948” n.d. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/urban-green-space/history/urban-green-space/1920-to-1948/ ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “Development of Urban Green Space in East Berlin, 1948 to 1990” n.d. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/urban-green-space/history/urban-green-space/east-berlin-1948-to-1990/ ↩︎

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “Development of Urban Green Space in West Berlin, 1948 to 1990” n.d. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/urban-green-space/history/urban-green-space/west-berlin-1948-to-1990/ ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. “Development of Urban Green Space in United Berlin since 1990” n.d. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/urban-green-space/history/urban-green-space/united-berlin-since-1990/ ↩︎