An initial theme that emerged was the discussion of Berlin’s housing crisis and development industries in the context of the field.

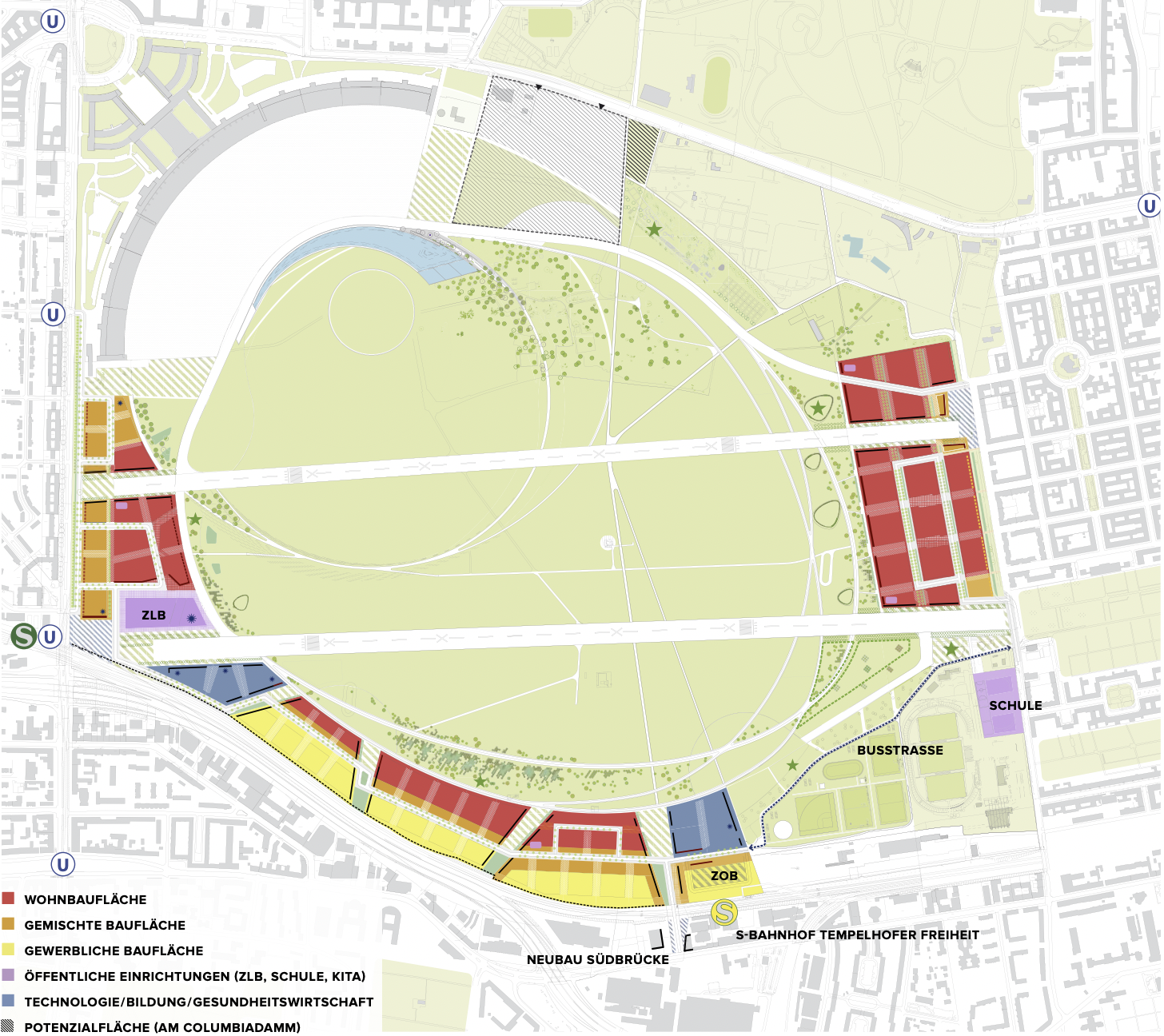

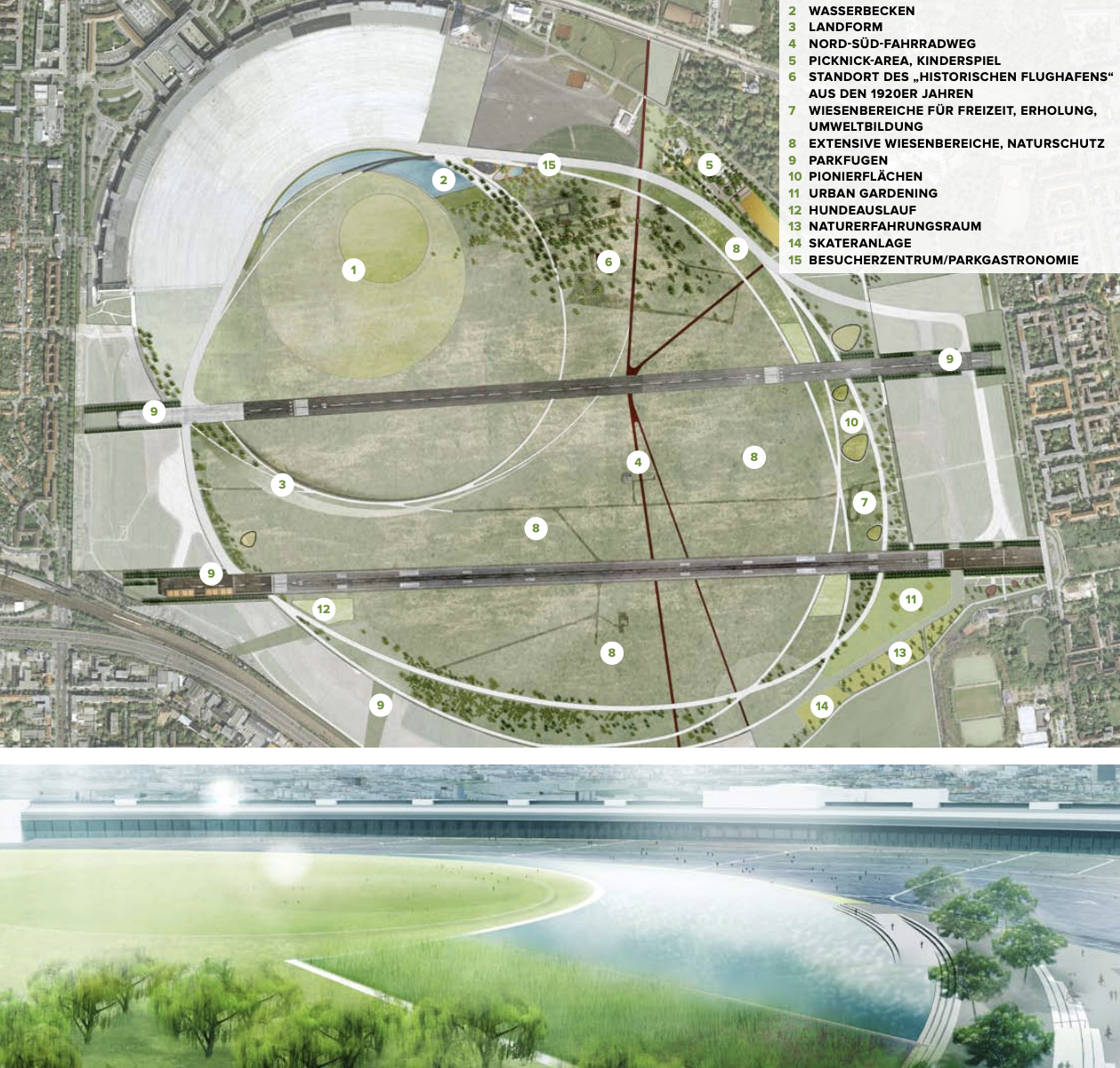

The Tempelhofer Freiheit Masterplan, developed after the closure of the airport to traffic, lays out a strategic groundwork for development of an urban European city. Between 2008 and 2014, the Senate Department for Urban Development and Environment’s Tempelhofer Freiheit project was aimed at development and revitalization of the space. The creation of the Tempelhof Freiheit Masterplan was supposed to be the result of a highly participatory process with citizens of Berlin. Initiatives began in 2007 through internet dialogue, and immense public interest was confirmed. Over 400 ideas for development were submitted, and thousands of comments were received. In 2009 a survey was sent to residents near the field to identify community needs, to which only a 25-30% response rate returned, however approximately 4,500 people attended an October participation event of that year.1 The landscape planning competitions began in March of 2010, with 6 selected proposals out of nearly 80 submitted. Called Pioneer Projects, these plans were intended to be clustered, temporary initiatives that support one another on the field. With high personal investment and low financial resources, the projects pay one Euro per square meter annually, and are allowed to derive commission on any commercial use; they cover all operation costs themselves.

This initial development proposal (Fig. 1) also includes a park landscape revival with a water basin to collect rainwater, a dog run, and recreation areas. The design by Scottish firm GROSS.MAX aims to preserve the character of the airport and create an “innovative” park with a variety of uses.2

These development plans were, however, stopped, as the Law to Protect Tempelhofer Feld (ThfG) was passed in 2014.

These plans show an initial intention of development amid a longstanding and contentious debate about public space, housing, and development in Berlin. While the Tempelhof Field is one of many places subjected to development interests in the city, responses to its development illustrate larger sentiments around urban change in the city.

René Kreichauf, a Professor of Urban Studies from Berlin spoke of perception of empty space and its “political legitimization” as a justification for development and solution to the housing crisis.4

“This idea of just like building, building, building, building, building, it’s definitely like only one portion of the solution in a housing market that is completely, you know, unequal…that has become completely immobile in a way because people do not move anymore, they don’t leave their house,” he says about Berlin’s housing market, “And at the same time, there is a lot of housing that is completely underused and it’s usually housing of the more wealthier”.5

Beyond already built and unoccupied housing, a 2019 report on urban housing development indicates space for 200,000 new units without ever touching the Tempelhof Field.6 Additionally, larger feelings of distrust and skepticism over government plans is palpable among Berlin residents. René spoke of a sentiment in the city developed over multiple decades, that previous housing developments and urban strategy by the government was hardly beneficial to the general public, and did not alleviate their concerns. So, with the introduction of a new development plan on the Tempelhof Field, “people knew that no matter what is going to be built, it’s not gonna benefit them”.7 This is also something I heard echoed in social situations, from professors, and in public media while living in Berlin.

“We need housing. We are in a housing crisis, but we also know whatever is gonna be developed by this government is not going to benefit us, but it will actually affect us negatively, especially in those areas that are already experiencing traumatic, you know, displacement, gentrification processes, etcetera.”8

Beyond distrust and skepticism towards government backed development, many people rebut the argument that this space is readily available for development. He says people feel that they’ve “made this empty space into like an exciting place to go for people in the neighborhoods, for people all over the city, for people visiting the city”.9 Residents recognized a need and still expressed that whatever the government’s plans were would not be beneficial for the field, community, or neighborhoods around it, or the goal of affordable housing. “It’s not gonna benefit the city. It’s not gonna benefit us”.10

The development cause is, however, quite strong. Large sections of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and Christian Democratic Union (CDU) political parties are well entangled with Berlin’s development lobby, and from a profit-driven perspective, “there’s thinking of Berlin as a place with empty space that is just waiting to be developed”.11 The coalition’s goal is to build 20,000 residential units each year in Berlin, and leaders of the parties have spoken out in favor of new referendums to allow development of Tempelhof Field.12 This narrative of ripe empty space is often used by politicians in Berlin, but also speaks to a more general trend in urban development narratives, says René.13 The reasoning used by both developers and politicians, “saying, well, it is an empty field and we have a housing crisis in Berlin and we have a refugee or migration crisis or whatever…so we have to use this huge, you know, area of empty space, like it would be completely nonsense to not use it”.14

“I don’t wanna say it’s like colonial thinking, but there’s thinking of Berlin as a place with empty space that is just waiting to be developed,” a perspective that many of Berlin’s residents strictly oppose.15

René challenged the mindset of development by pointing out that this so-called emptiness is an illusion, and that in fact the space is not empty, it’s just empty of high profit yield activity:

“The problem obviously is that the field is not empty. There are things. Well, there are physical things at the field. There is ecology, there is habitat on that field. There are different forms of usages on this field and not even like on a good, sunny day. Even on a very ugly day, there are people on that field using that field, and that field is never really empty, not even in the middle of the night when they are trying to close it. You know, it’s never really empty.”16

First Chairman of Community Garden Allmende-Kontor (AK), Juan Coka Arcos echoed René’s remarks about distrust of development: “they say they are gonna build like social spaces, social buildings, but yeah, at the end, we all know that this is not going to happen”.17 While René spoke of larger trends in urban development, Juan’s main concern is the garden in which he works. “The garden and the park… is going to lose a lot of diversity,” not just biodiversity, but diversity of persons pushed out through gentrification if the field is developed.18

“This part of Neukölln is, is, is suffering a lot of the gentrification and this gentrification we can also see in the garden.“19

These larger urban development narratives were salient within the community-garden specific context on Tempelhof Field. The Allmende-Kontor garden is located on the Eastern side of Tempelhof, adjoining the historically immigrant and working-class neighborhood of Neukölln. “Right now, this part of Neukölln is, is, is suffering a lot of the gentrification and this gentrification we can also see in the garden,” said Juan.20 When he began gardening in 2016, the gardeners came from diverse cultural backgrounds, and now, he says it has changed to be much whiter, more student-heavy, and less culturally diverse.21 The number of gardeners has increased heavily since their beginning in 2011, and while having people who want to be part of the garden is “awesome”, it comes with its challenges; one of which is “losing this part of cultural diversity”.22 He says new student involvement can be more difficult to retain, “they’re just like, I have my piece of land and I’m working there. Then one year, one year later, they are not. They are not anymore there”.23 And because Allmende-Kontor is a community garden, people who join should also be part of the community not just the garden.

Despite his specific comments on the demographics of gardeners, Juan notes how the field reflects Berlin as a whole:

“but at the end, it is also how the city is developing. And, you know, Berlin is always changing”.24

- “Activation of an urban open space through citizen participation.” Urban Sustainability Exchange, n.d. https://use.metropolis.org/case-studies/germany-berlin-tempelhofer-freiheit-urban-open-space ↩︎

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt. Freiraum für die Stadt von Morgen. Tempelhofer Freiheit. 2013: 3. https://use.metropolis.org/system/images/1038/original/tempelhofer_freiheit.pdf ↩︎

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt. Freiraum für die Stadt von Morgen. Tempelhofer Freiheit. 2013: 3. https://use.metropolis.org/system/images/1038/original/tempelhofer_freiheit.pdf ↩︎

- René Kreichauf, Microsoft Teams interview with Clara Feldman, December 5, 2023.

↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Harrison, Anne-Marie. “Why Does Berlin Keep Trying to Build Housing on Tempelhofer Feld?” *The Berliner*, November 9, 2023. https://www.exberliner.com/politics/berlin-housing-crisis-referendum-refugee-building-on-tempelhofer-feld/. ↩︎

- René Kreichauf, Microsoft Teams interview with Clara Feldman, December 5, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Hackenbruch, Felix, and Anna Thewalt. “Koalitionsverhandlungen in Berlin: Cdu Und SPD Einigen Sich Auf Randbebauung Am Tempelhofer Feld.” Aktuelle News: Nachrichten aus Berlin und der Welt, March 24, 2023. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/koalitionsverhandlungen-in-berlin-cdu-und-spd-einigen-sich-auf-randbebauung-von-tempelhofer-feld-9556895.html. ↩︎

- René Kreichauf, Microsoft Teams interview with Clara Feldman, December 5, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎