While interviews centered on the personal uses and meaning of the field, the topic of the field’s potential development was constantly looming. Interviewees frequently and independently brought up the ongoing conflict over the field’s development and use, as well as the political situation in Berlin surrounding its status. As discussed, larger themes of urban change are apparent in users and activity on the field, and influence how people think about the space. I found the field to also reflect many historical, civic, political, and temporary processes beyond its fences.

It was not the focus of the research to investigate the currently unfolding political debates over the use of the field, but the processes identified here constituted important parts of understanding what the field means to its users.

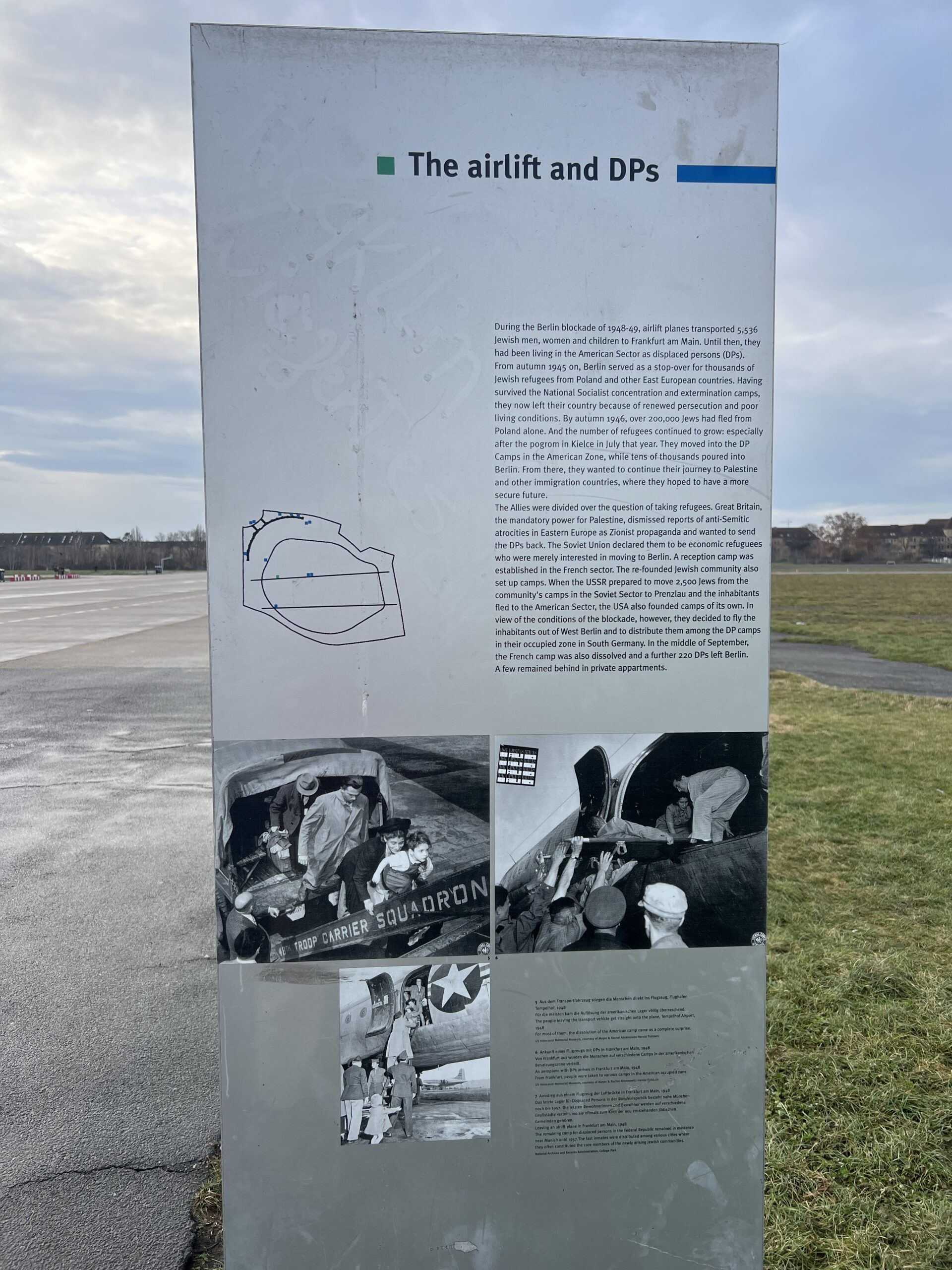

Firstly, Tempelhof Field hosts a variety of historical processes, and as an active site of preservation on account of its “cultural and historical significance”, it’s a site of current history making.1 The Law to Protect the Tempelhof Field does so for multiple reasons, two of which being its “unique “ensemble” of landscape elements that bear witness to the history of the area,” and its standing as, “an occasion to commemorate victims of National Socialism on areas of the field where human rights violations occurred,” referring to the extensive military use that occurred on the field during and after the Second World War.2 Multiple instances of commemoration are visible on the field, including the history walk, which tells a historical recount of the site over time through large timeline structures.

Additionally, less explicit ways of commemorating history, and living history in the making can be experienced on the site. The existing tarmacs, hangar building, various buildings, and a singular decommissioned airplane all serve as reminders of the field’s airport history. Walking the tarmac retraces the steps of planes that took their first flights, balloon launches, and iterative landings of American cargo planes during the Berlin Airlift. The grasslands bear witness to the natural history that has remained on the site since the city began to rise around it. And the soil still holds the chemical imprint of the site’s many previous uses.

Its current use is also a reminder of the ongoing migration processes unfolding in Berlin and much of Europe. An amendment to the protection law, which allowed for the temporary installment and use of refugee housing infrastructure in the hangar building and the tarmac bear witness to past, present, and future migration through Berlin. Currently, a small village of converted shipping containers sits as a refugee housing space, dubbed “Containerdorf” (Container village). As an expert on urban studies and migration, René found this part of the field to be very meaningful and illustrative of his home city:

“I remember passing the Containerdorf several times and nobody was living in there and it was kind of like, to a certain degree, it was a relic of the past, but it was also like a sign of the future to come in a way, because it was quite clear that if there will be another huge arrival of people, it will be used again, even though politicians were not saying it was always like, ohh, no, we’re gonna deconstruct it.“3

For many, the use of the field for political and social purposes related to international issues is a departure form their personal recreation uses, but remains an important facet of how the city interacts with the space.

The container structures are also a reminder of a reality that many users of the field are accustomed to: temporariness. Temporary residents on the site are not the only ones subject to impermanence. Allmende-Kontor (AK) and other projects are introduced and implemented with the understanding that their tenancy on the field can end. Allmende-Kontor, for example, has a contract that forbids them from digging into the ground, which is the reason for their raised beds. They are also not allowed to plant trees, although many trees are growing through normal succession, and so they will likely reach that privilege eventually, said Kristin.4 “We’re still only temporary,” said Kristin, but in contrast to their first few annual contracts, Allmende-Kontor now signs five year space contracts, indicating the growing permanence of their presence.5

Similarly to Pioneer Projects, the refugee housing was introduced as something strictly transient, said René, “the plans to use the space to accommodate refugees has always been kind of like, sold as a temporary situation, but this situation has been going on for eight years now, so it is a permanent situation”.6

“What was meant to be temporary…emerge to be permanent,” says René, speaking of the introduction of the use of the tarmac space for housing.7 This emerging permanence is enacted daily by consistent use of the field’s Pioneer Projects, too, where structures are built on the site for learning and gardening purposes.

The civic and political processes that occur on the site are also of great interest to those who use it. Often, impermanence is central to great fear about the future of the field. While many years of civic involvement went into passing the referendum to protect the Tempelhof Field in 2014, political groups and private interests have been looking for ways to pursue their interests. This is the center of current debates about the field, impermanence, however theoretical, of its current uses predicates the potential for eventual development. The law stands to protect the field at this time, and a campaign to have it designated a UNESCO World Heritage site is underway. But some political groups are also looking to overturn the protection and allow development, as proposed after the airport’s initial closure.

What these current issues have shown is that the field is the site of many of these political debates and discourses. It is in some ways, a physical manifestation of larger political discourses surrounding sustainability, democracy, and general political strife.

The Field Coordination is a liaison body of 11 representatives (7 citizens, 2 senate representatives, and 2 GrünBerlin representatives), meant to ensure openness and cooperation between citizens and politicians regarding the field.8 This infrastructure aims to democratize involvement in determining field management and future. Juan mentioned the coordination group specifically as a key tool for navigating the topic of field development, where they’re “doing a lot of meetings” to discuss the future of the field.9 He and other project leaders “are trying to connect with the other initiatives and also with the civil society to make people aware that what the government of Berlin is doing right now, it is not sustainable for the future for Berlin”.10 Kristin regularly attends demonstrations on behalf of the garden, as well as herself, to protest alongside many Berliners against threats to the field’s protected status.11 Everyone I spoke to referred to the threats facing the field as part of the “political situation”, indicating that multiple spheres of civic and political life are interacting on the site.

A sign posted at Allmende Kontor’s bulletin board reads:

“We love the Tempelhof Field. You too?”

The sign shares information on the Field Coordination group and citizen involvement

Photo by Clara Feldman, December 2022.

Juan is staunchly against development on the space, and feels serious disappointment in the city of Berlin “from the political side,” because Berliners “already gave our vote, dnd they don’t, they are not taking this into consideration. Because right now, they’re just decided to change the law”.12 The law has not been changed, but remains challenged and could face a second referendum.

“I think we are gonna give our best to secure the Tempelhofer Feld, we are trying it. I hope that the political things in Berlin take a responsible decision, and to know that for the future, the park is a key urban space.“13

- Gesetz zum Erhalt des Tempelhofer Feldes (ThF-Gesetz), June 14, 2014: 3 ↩︎

- Ibid., 3. ↩︎

- René Kreichauf, Microsoft Teams interview with Clara Feldman, December 5, 2023. ↩︎

- Kristin Hensel, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 11, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- René Kreichauf, Microsoft Teams interview with Clara Feldman, December 5, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Beteiligungsmodell Tempelhofer Feld.” Beteiligungsmodell Tempelhofer Feld – Tempelhofer Feld, n.d. https://tempelhofer-feld.berlin.de/beteiligungsmodell-thf/. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Kristin Hensel, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 11, 2023. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎