Collecting and organizing information on the personal meanings of the field was a large part of the findings. Overwhelmingly, personal ideals and values were employed to express people’s understanding of the meaning of the field, and often within contexts of threat to the space itself. In naming what people did on the field, they also tended to name why they did those things and what ideals or values of theirs it aligned.

Ideals were subcategorized and examined under the identifiers of: diversity, freedom, aesthetic, responsibility, and community. All of these are ideals people named directly or referred to by naming similar things that they value on the field. Using these markers, I was able to better organize information on how people spoke of their work on the field and their relations to it, as well as what it meant to them personally.

Diverse city life and culture unfold here–understood in a broader sense of freedom, openness, tolerance, coexistence and ultimately participation and democracy.1

Overwhelmingly, people spoke of the diversity offered at Tempelhof Field. While I initially had not divided diversity further than a single subcategory, it emerged that diversity was either spoken of in terms of diverse offerings on the field (such as activities and events), or diversity of people. Juan Coka Arcos stated it was, “very difficult to describe what does it means to me, and also what does it means to the city because at the end, it is so diverse”.2

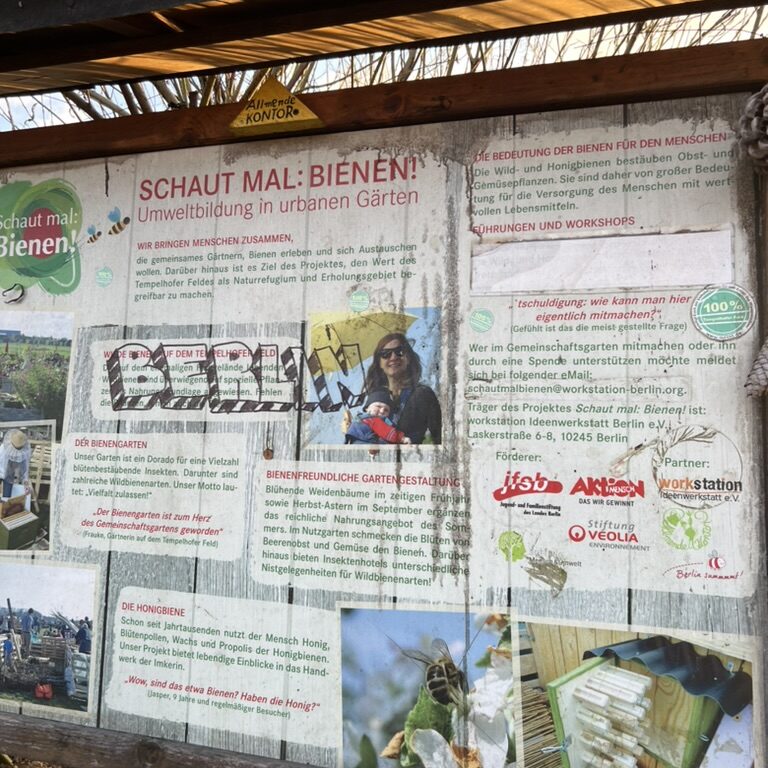

Juan, besides being a member of the AK Vorstand (board), is also one of the group’s beekeepers. His responsibilities are diverse, acting as a board member to fulfill bureaucratic requirements of the Pioneer Project, gardening and tending to the beehives, organizing volunteer work, and using the garden for his own personal social, relaxation, or recreation needs.

Communications and publicity lead for Allmende Kontor (AK), Kristin Hensel shared a similar sentiment, noting that:

“the field offers a lot of freedom, also in a wide variety of activities. That’s what makes Berlin so special.”3

“ja, also das Feld, was da halt eben sehr viel Freiraum bietet, auch in unterschiedlichsten Aktivitäten. Das macht halt vor allem Berlin aus.”4

Kristin and Juan are both gardeners, but both named using the space for social gatherings, taking time alone, relaxation, and enjoyment of nature—among other recreatory uses. Juan often reiterated how much he liked this diversity of opportunity, that it is always good to have “a big space in the city where you can do so much different stuff”.5

A variety of Pioneer Projects, of which Allmende Kontor is one, are examples of urban re-use. Given the opportunity and space, diverse Pioneer Projects such as the M.I.N.T Green Classroom, Lernort Natur, and sports groups provide city residents and visitors with diverse activity offerings. The Maintenance and Development Plan (EPP) for the field, created at the order of the Law to Protect Tempelhofer Feld (ThfG), lays out this inherent opportunity and diverse innovation in one of its 10 guidelines. This guideline of free space says, “The field enables innovations in the areas of culture, recreation, sport and exercise, encounters and interaction as well as inclusion and integration. The Tempelhofer Feld, while respecting its specific character and the defined protection goals, is a place of enabling culture, the implementation of which can take place in many different cultural forms of expression and formats”.6

It is clear that the possible diverse activities are valued in their own right, but further, this recreational diversity is intertwined with a demographic diversity of the field’s users–which is something named as important to my interviewees. The study conducted by the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research on the social value of Tempelhof Field names this diversity as central to the space’s role as a facilitator of social connection and diversity of users, offering chances for community activities between various social and cultural groups.7 Not only does this diversity of activity stand alone as a meaningful ideal for users of the field, but it goes hand in hand with a demographic diversity on the site. The field is a “diverse and ever-changing space of opportunity”.8

Integral to this diversity is the accessibility of the field, where Section 3 of the ThfG ensures “barrier-free movement”, and “accessibility without exception”.9 The EPP’s additional guidelines state that “Accessibility, inclusion, equal opportunities and the needs of all user groups” be taken into account in all development and maintenance action plans.10 It is declared a “public, non-commercial space for all people regardless of age, gender, religion, nationality, origin or social status”.11 Overall the EPP aims to ensure unrestricted and equitable access to all who step onto the field so that diversity of activity and people may flourish.

The accessibility measures, as well as the openness and space of the field, enable a diverse spattering of recreational activities and users.12 As one of many diverse uses, Allmende Kontor has made diversity of users central to their organization. Their organization statute is based on the idea that community gardens take on a multidimensional function in urban living spaces.13 Their website reiterates, stating their contribution to a diverse urban society, “intercultural gardens pose and answer central questions of urban society: about social, cultural and biological diversity, participatory urban design, urban ecology, supply and consumption, education, exercise, nutrition and health, solidarity, integration and civic engagement.”14

Related to, but named differently from diversity, was the ideal of freedom. Interviewees spoke of the importance of feeling free and having a sense of freedom through their activities on the field.

Because the field is of an enormous size, you have more space and “freedom to do things,” said René. Juan noted that one of his favorite things about the field was a sense of freedom that allowed him to disconnect from the stress of his day-to-day. After leaving what he called the “hustle” of Berlin life, “suddenly you are in this open space, and you feel free, you feel like—you feel free, you know, for me, because you can see the horizon, that’s why for me, it’s kind of a way to just to think a little bit more about things, reflect about my day sometimes also”.15

The character of the field was often named in conjunction with this feeling of freedom for interviewees. Kristin spoke of the freeing quality of having such a big space with natural qualities, and that the the “agricultural use” (grasslands, grazable areas, avian breeding grounds, etc), “there in the middle of the city,” is what makes it “possible to have the feeling of country, nature and freedom in the middle of the city”.16 This was one of her favorite things, particularly in the context of the garden—a place to get some freedom from the city. The field as it stands today, with diverse groups and activities and programs, would not exist “if there wasn’t such a large area that could be used freely,” says Kristin.17

Freedom extended beyond activity and movement for Kristin, and she named the freedom AK had to build its aesthetic and community alternatively to the city around it as a very important aspect to her. The aesthetic of AK she said is, “known for being very crooked and lopsided and very chaotic”.18 While maintaining a conscious approach to their growth, freedom of alternative expression is important, posing the question: “how do we imagine the city? Not gray and clear and straight, but diversity in the form of shape and unevenness”.19

The idea of community was valued highly among interviewees and throughout research. When speaking to both members of the community garden, they had specific reasons to value community greatly. This is, of course, entangled with their programming and activity, but also something they spoke of as being valued personally. Juan enumerated the ways AK aims to bring in new members and foster a sense of community.20 The garden, which is open to all, continually looks to adapt and foster community among new people who join to “be part of garden and not just to have their slot, but to get involved”.21 They do this through a variety of educational and community programming, but ultimately for Juan the community is what he values most. For him it’s a sense of community and connection: “at the end, for me, that is the most beautiful part of it, besides gardening, to get involved with other persons, and with the park, not just with a garden with the park, but with the space”.22 He’s gained new friends and a new network of co-volunteers through his time there. Specifically in bee-keeping, where his fellow bee-keepers began as amateurs and learned together, now watching multiple hives annually. “We are good friends. And we have this common thing that we, we are interested about bees and we yeah, we share this passion…and this is super nice,” said Juan.23

- Brenck et al. “Gesellschaftliche Wertigkeit des Tempelhofer Feldes – Qualitäten erfassen und sichtbar machen.” Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung GmbH – UFZ, November 2021. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Kristin Hensel, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 11, 2023. ↩︎

- Kristin Hensel, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 11, 2023. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt. Entwicklungs- und Pflegeplan Tempelhofer Feld. Berlin, Germany, May 2016: 14. ↩︎

- Brenck et al. “Gesellschaftliche Wertigkeit des Tempelhofer Feldes – Qualitäten erfassen und sichtbar machen.” Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung GmbH – UFZ, November 2021: 56. ↩︎

- Ibid., 75. ↩︎

- Gesetz zum Erhalt des Tempelhofer Feldes (ThF-Gesetz), June 14, 2014: 190. ↩︎

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt. Entwicklungs- und Pflegeplan Tempelhofer Feld. Berlin, Germany, May 2016: 14. ↩︎

- Ibid., 14. ↩︎

- Ibid., 24. ↩︎

- Allmende-Kontor e.V. “Satzung des Gemeinschaftsgartens Allmende-Kontor.” Berlin. December, 2016. ↩︎

- “Allmende-Kontor Community Garden on Tempelhofer Feld.” www.tempelhoferfeld.de, n.d. https://www.tempelhoferfeld.de/en/discoveries-experiences/civic-engagement-projects/community-garden-allmende-kontor/. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Kristin Hensel, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 11, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Juan Coka Arcos, Zoom interview with Clara Feldman, November 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎